Webinar: COVID-19 & HBOT: What We Know and What We Don’t

May 6, 2020Using Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Coronavirus Lung Infection: The time for more HBOT treatment and studies is now. Completed IRB application and consent enclosed.

May 9, 2020James BP. Intermittent high dosage oxygen treats COVID-19 infection: the Chinese studies.

Letter to the Editor of Med Gas Res 2020;10(2):0-0.

Dear Editor,

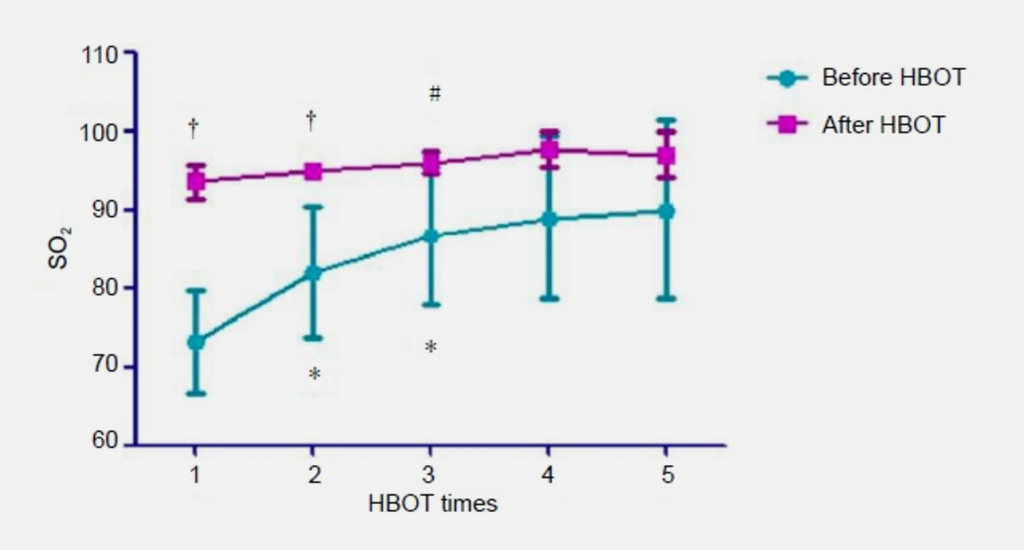

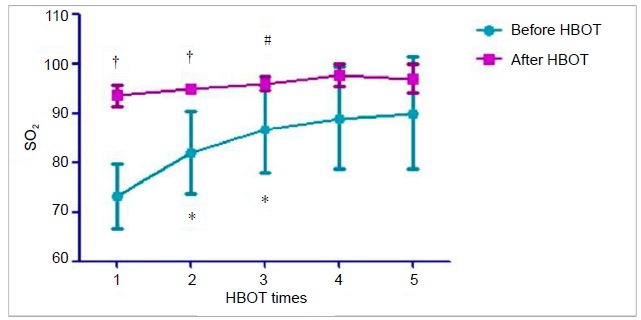

Dr. Paul Harch reproduced a graph of oxygen saturations of just five patients in his excellent commentary1 on two Chinese studies.2,3 They have provided definitive evidence from measurements of oxygen saturation that intermittent high dosages of oxygen are the key to the successful treatment of COVID-19 infections.

The lung pathology associated with infection by COVID-19 produces a “ground glass” appearance on chest X radiographs typical of the diffuse interstitial oedema seen in drowning and high altitude pulmonary oedema. As in these patients, those with COVID-19 infection will have reduced oxygen diffusion across the alveolar membrane. This is clearly evident in the measurements in the Chinese studies before treatment where the range is from 65% to 80% with the patients on supplemental oxygen.

The data in Figure 1 of Harch’s article1 indicates that:

- There is increased diffusional resistance to oxygen in CO- VID-19 patients – hence the very low oxygen saturations on supplemental oxygen.

- The resistance can be overcome by using high concentrations of oxygen in a simple pressure enclosure.

- An increment of improvement is sustained with each session.

- The improvement shows that oxygen is treating the underlying pathology and resolving the oedema.

- Oxygen is therefore being used as a treatment not a simple blood supplement.

In healthy young adults (15–21 years) the alveolar partial pressure/arterial oxygen tension difference at sea level is about 5 mm Hg whereas in older people (61–75 years) it is typically 16 mm Hg.4 Young people normally maintain an oxygen saturation of 95–100% which translates into a plasma tension of 100 mm Hg. An older patient with a saturation of 85% has a plasma oxygen tension of only 55 mm Hg and this may be accompanied by tissue hypoxia. In the presence of a proven oxygen deficiency it is not ethical to withhold additional oxygen and at the correct dosage which the Chinese studies have shown by measurements may need the use of a pressure chamber. The precedent was set at Ypres, Belgian in 1915 by Haldane5 treating Allied soldiers with 100% oxygen for lung damage from being gassed by chlorine.

Figure 1: Daily mean blood oxygen saturation levels before and after each HBOT in five COVID-19 patients.

Figure 1: Daily mean blood oxygen saturation levels before and after each HBOT in five COVID-19 patients.

Note: Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, vs. pre-first HBOT; #P < 0.05, vs. post-first HBOT; †P < 0.05, vs. pre-HBOT for that day. HBOT: Hyperbaric oxygen treatments; SO2: oxygen saturation. Reprinted with permission from Harch.1

Tissue hypoxia leads to further inflammation from the attraction of neutrophils.6 The vicious cycle where inflammation is tied to hypoxia7 can only be broken by an increase in the oxygen available to tissues.8 Intubation and positive pressure ventilation causes micro-trauma to already damaged lung tissue and extra corporeal membrane oxygenation is complex, highly invasive and does not treat the pulmonary pathology. All the patients treated in China using pressure chambers recovered and no side effects were reported. Basic pressure chambers are used in every country of the World to transport people: Business jet aircraft can provide additional pressure needed whilst on the ground and simple equipment can be installed to provide 100% oxygen.9 This can transform the treatment of the most seriously affected COVID-19 patients and the thousands of aircraft marooned at airports by the current crisis can be put to good use as “Nightingale” wards.

Philip B. James*

Department of Surgery, University of Dundee, Scotland, UK

*Correspondence to: Philip B. James, MB, ChB, DIH, PhD, FFOM, pbjames1942@gmail.com.

orcid: 0000-0002-4056-8130 (Philip B. James)

doi:

How to cite this article: James BP. Intermittent high dosage oxygen treats COVID-19 infection: the Chinese studies. Med Gas Res 2020;10(2):0-0. Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by the author before publication.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement: This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropri- ate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

RefeRences

1. Harch PG. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment of novel coronavirus (CO- VID-19) respiratory failure. Med Gas Res. 2020. doi: 10.4103/2045- 9912.282177.

2. Zhong X, Tao X, Tang Y, Chen R. The outcomes of hyperbaric oxygen therapy to retrieve hypoxemia of severe novel coronavirus pneumonia: first case report. Zhonghua Hanghai Yixue yu Gaoqiya Yixue Zazhi. 2020. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-6906.2020.0001.

3. Zhong XL, Niu XQ, Tao XL, Chen RY, Liang Y, Tang YC. The first case of HBOT in critically ill endotracheal intubation patient with COVID-19. Beijing, China: Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Research Network Sharing Platform of China Association for Science and Tech- nology. 2020.

4. Mellemgaard K. The alveolar-arterial oxygen difference: its size and components in normal man. Acta Physiol Scand. 1966;67:10-20.

5. Haldane JS. The therapeutic administration of oxygen. Br Med J.

1917;1:181-183.

6. Zamboni WA, Roth AC, Russell RC, Graham B, Suchy H, Kucan JO.

Morphologic analysis of the microcirculation during reperfusion of ischemic skeletal muscle and the effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:1110-1123.

7. Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:656-665.

8. Abbot NC, Beck JS, Carnochan FM, et al. Effect of hyperoxia at 1 and 2 ATA on hypoxia and hypercapnia in human skin during experimental inflammation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1994;77:767-773.

9. James PB. Oxygen and the brain: The journey of our lifetime. North Palm Beach, FL, USA: Best Publishing Co.

page1image2440494000

© 2020 Medical Gas Research | Published by Wolters Kluwer – Medknow[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]