A 33-year-old drunk driver wraps his pick-up truck around a tree and is brought to the emergency room at a small, community hospital in Slidell, Louisiana. His emergency room doctor, Dr. Paul Harch, recalled the scene. “You know, high-speed, straight into a pick-up, no seatbelt, and the flexion injury rendered him paralyzed immediately. By the time they got him off the floorboard of the truck…he had a flicker of movement in his one big toe; within forty minutes he was densely paraplegic. At three in the morning the neurosurgeon, radiologist and myself looked at each other…and the only explanation was that he had a vascular injury to his spinal cord. And almost in unison we said, “Gosh, I wonder what he could do with a little oxygen?” I put him in the hyperbaric chamber and he moved his toe. When we took him out, he had sensation down in the foot. Incrementally, every time I put him in, he got more and more sensation. In seventeen days, he walked out of the hospital. That just blew everybody away.”

Harch, a physician at the Louisiana State University Medical Center and Inaugural (past) President of the International Hyperbaric Medicine Association, has been treating patients in hyperbarics since 1985. Patients are dosed with high-pressure oxygen by placing them in a decompression chamber, a treatment usually associated with scuba divers with decompression sickness. Harch, 53, who trained at Johns Hopkins University had “some very high aspirations.” Unfortunately, after starting his internship in general surgery, he was hit by a car and badly injured in the accident, derailing his career plans. He ended up doing emergency medicine in Slidell, 90 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Disappointed with the direction his career was taking, he nearly quit medicine. He gave notice and told his colleagues he was looking to make his mark elsewhere. But after he “decided to quit my pissing and moaning,” he realized that he was intrigued by decompression illness, and curious about the fact that there was no literature on diver neurology.

“Everybody thinks of decompression sickness as the bends –joint pain, bent over, and so on. In fact, three-quarters to four-fifths of all decompression sickness is neurological—mostly spinal cord, but a good proportion of that is brain-based. Eight and a half decades of diving medicine and nobody could answer some simple questions about what was going on in the brain…an opportunity was being presented to me that I couldn’t walk away from – to change and revolutionize the treatment of brain injury.”

Until recently, most scientists believed that the brain contained a finite number of cells, depleted over the course of human life. However, recent research has overturned that idea. The most important findings have implied that two factors are required for brain cell growth – not crossword puzzles and not advanced math, thankfully – but sufficient sleep and exercise. Dr. Astrid Bjørnebekk found that exercise stimulates the production of new brain cells (reported in ScienceDaily, June 29, 2007). Bjørnebekk’s study aimed to decrease depression through exercise, which increases blood flow to the brain. Scientists believe this sea change signals future relief of human suffering for a variety of “incurable” neurological ailments – Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, and chronic Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).

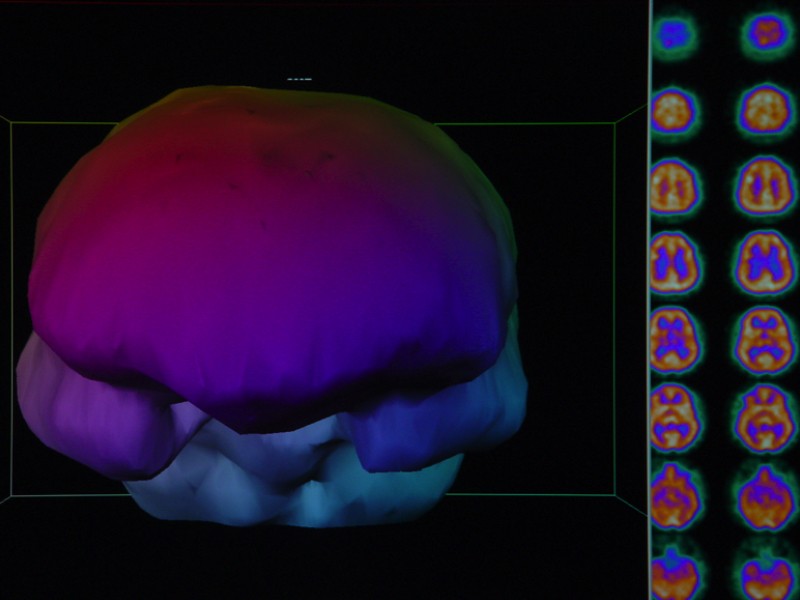

So how did Harch reach his seemingly zany conclusion? In the late 80’s, Harch realized divers were coming to him with symptoms of decompression sickness long after diving, and no longer had the nitrogen bubbles in their systems that cause decompression illness. Further study led him to believe that what he was observing was low blood-flow brain injury. Harch conducted experiments using lower-pressure hyperbaric oxygen treatments (HBOT) over longer time spans. Soon Harch was using the new protocol to treat a variety of neurological problems, including chronic TBI, Cerebral Palsy, Autism, and Stroke. Time after time, Harch saw improvement in the cognitive function of his patients and in brain blood flow scans (SPECT images) of patients’ brains.

Harch put his clinical procedure under an experimental protocol for six years: a SPECT scan, one hyperbaric treatment, followed by another scan, to compare for improvement in brain blood flow. Then he treated people in blocks of forty treatments, to assess response, and indexed it to imaging and other clinical indicators. He found that the imaging predicted who would improve. After a while, he didn’t even need imaging because so many people responded to the treatment; it was reproducible. As Harch began to present his research, he realized that scientists didn’t want to believe his findings “because they violated 100 years of neurology.”

Seeking to silence his critics, Harch embarked on a series of animal studies. His funding was minimal and came in the form of a $50,000 gift from Louis Ross, a patient’s husband who owned a dairy. In the first twelve rats studied, the team had statistically significant results, but the physiologist who designed the research model refused to publish it, believing the data was “flukey.” Harch’s team repeated the study with thirty rats, but a malfunction of the lab equipment nixed the results. They then planned a study using five times the original number of rats. This study coincided with a heat wave in New Orleans in July 1998. The rats were shipped in an un-air-conditioned van and expired before they reached the lab.

Finally, in 2001, the team’s animal research generated very powerful results, even more so than the previous pilot trial. “But they sat on it for a couple of years trying to find what we had done wrong—-it was like the O.J. trial, you know?…Here we had all these positive results, but they just knew something had to be wrong with the methodology. It was a fifteen-year-old model when we started in 1994. It finally got published and that was last year (2007).”

Finally, after 17 years, the findings were published in Brain Research.[i] They describe a ground-breaking improvement of chronic brain injury in animals. Results were impressive, and reconfirmed their treatment outcomes with human patients. The researchers measured the vascular density of the rats’ brains where the injury occurred, and correlated this with the rats’ cognitive performance. In comparison to the two control groups, the group treated with HBOT showed markedly improved vascular density in the injured area, which was associated with improved cognitive performance. In other words, Harch and his colleagues found that HBOT significantly increased blood volume and flow to the affected brain areas and that helped the rats regain some of their lost function.

Dr. Gary K. Steinberg, Chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at Stanford University School of Medicine warns, “I would be cautious about drawing any definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen for treating neurologic disease, including TBI. The preclinical (animal) results are equivocal and the clinical reports only anecdotal. Although the treatment appears safe, further controlled studies in patients are required before it can be recommended as beneficial therapy.”

Insurgents drove a truck laden with 2,000 pounds of explosives into the building where the Marines were holed-up in the middle of Ramadi. Most of the guys in the detachment were knocked out by the massive explosion. In no time, they were under attack and outnumbered by seventy-eight insurgents to their thirty-three – needing help, some of the soldiers were shaking a young man to rouse him from his unconscious state. He regained consciousness, sat up, and they were hit with the second explosion – a rocket-propelled grenade against the wall. The Marine lost consciousness for the second time in fifteen seconds.

“Whenever there’s an explosion like that, on the opposite side of the wall, everybody’s knocked out. It’s similar to what happens with concussive explosions and hollow viscouses in our body, lungs and intestines; the shock force does greater damage at the air-tissue interface. So he wakes up and he’s in the middle of a fire-fight…a minimum of seven hours or so… cerebral dysfunction is not appreciated because you’re in a war zone—it’s heightened awareness, poor sleep…hyper-vigilance. It’s not until they get home that…the effects of the brain injury become manifest.”

Apart from giving drunk drivers a second chance, Harch’s findings have important implications for Iraq War veterans. As many as 400,000 veterans have been exposed to concussive force and possibly suffered a TBI. According to one patient—a Marine—every man in his thousand-man battalion has been exposed to IED’s and a minimum of 50% have been knocked unconscious. Harch: “It’s considered a non-injury. You’re a wimp if you have symptoms. Unless you’re bleeding or have had an appendage blown away, or lost an eye, you’re not considered injured.”

TBI affects over 1.4 million Americans annually. The leading cause is falls, followed by motor vehicle crashes.[ii] Moreover, blasts are a leading cause for active duty military personnel. Called the “signature injury” of the Iraq War, some accounts estimate that up to 60% of injuries related to roadside bombs in Iraq are TBIs. Symptoms include memory loss and communication problems; even worse, perhaps, are the behavioral and psychological ramifications. Formerly balanced, responsible and mature adults may become impulsive, irrational, and depressed.

Harch recounted several stories about patients who had become psychologically dysfunctional, “demented,” “suicidal,” “violent” and “a throw-away.” Some patients were institutionalized, diagnosed as untreatable. One commercial diver was refused medical coverage by the company doctor who ruled that his injury as a result of diving was inconclusive. The patient loaded two pistols and went to the company headquarters in New Orleans. Luckily, he called his brother to say good-bye; his brother intervened and put him into treatment with Harch. The patient is now functional and Harch was able to prove his medical case to the company with SPECT imaging.

The U.S. military command does not appear to be interested in HBOT. Harch and a colleague submitted separate grant proposals to the military and were turned down. Harch said, “We went to the top guy in the Army who oversees the brain injury program…and it was a very depressing yet enlightening discussion. It went nowhere…it was surprising, the response we got.”

Brigadier General Patt Maney was told he is the highest ranking soldier wounded in Afghanistan by a roadside bomb to survive a TBI. A state court judge in Florida,

Maney was called up to service in his capacity as an Army Reservist. Maney said that in addition to TBI, soldiers frequently suffer other physical injuries, like wounds from shrapnel, loss of limbs, burns, and broken teeth –“polytrauma.”

Maney was treated one year after his injury using the Harch-prescribed HBOT protocol at George Washington University Hospital. Describing his experience, Maney said, “The treatments are easy if one doesn’t have a problem with claustrophobia. Some hyperbaric facilities have multiple person chambers but GW uses one-person chambers. The chambers are clear cylinders with closed ends. A patient is slid into the tube and the end is closed. A technician or physician stays outside the chamber but with the patient the entire time. Initially, I watched television during the [one-hour] dives but as I got more accustomed to the dives, I frequently napped.”

Maney said that his wife noticed improvements in his cognition following 8-12 dives, while he observed improvements after 12-14 dives. After 20 dives, his friends commented that he seemed more socially engaged. “From my experience, I believe that HBOT should be the foundational treatment for all soldiers with a TBI. It’s really disappointing that some military medical practitioners decline to recognize the documented scientific advances, possibilities and results of HBOT. The TBI wounded and their families need effective treatment now.”

A 2006 study (Finkelstein et al) states that costs related to TBI totaled $60 billion in the year 2000 – actual medical costs as well as lost productivity. This includes over 5.3 million TBI survivors who need ongoing help to carry out the daily activities of living. One of the major advantages of HBOT is its relatively low cost; 40 sessions of HBOT cost about $4,000. Compare this to the financial and human costs of institutionalizing a young person for 40 years. In 2002, Harch testified to Congress about the costs of HBOT relative to taking care of the untreated. “Forty percent of my practice is neurologically injured children…who cost on average, 2.1 times as much to educate as a non-injured child. There are 6.548 million…children in the nation…[which cost taxpayers]…a total of $55.7 billion. For many of these children, if they had been treated immediately upon injury, the costs drop to often less than $1,000.”[iii]

Of the many who suffer a TBI annually, 50,000 die, 235,000 are hospitalized, and 1.1 million are treated and released from hospital emergency rooms. The typical person affected is young and male. One patient who fits the profile is 17-year-old Curt Allen, Jr., injured in a 2004 automobile accident. Video details the young man’s presentation following rehabilitation in “the best residential facility in the state of Louisiana,” from which he was dismissed for failure to progress. As he receives HBOT, Allen’s condition improves from practically non-responsive to walking, joking and talking.

Harch is currently involved in a ten-year stroke study while he continues to pursue funding to conduct human trials for chronic TBI. “The most important thing to know is that this is a generic drug for growth and repair of brain injury—both acute and chronic. Don’t wait for your doctors to come around to understanding this. It’s a low-risk treatment. Go out and seek a physician at a facility who will do this. Get this treatment for you or your loved one.”

[i] Brain research. 2007 Oct 12;1174:120-9.

[ii] Centers for Disease Control.

[iii] Harch, P., President, International Hyperbaric Medical Association (May 2, 2002). The impact of hyperbaric medicine on Government health care, disbility and education expenditures. Testimony to the Health and Human Services and Education Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, U.S. House of Representatives.